from 64 PARISHES:

An Oasis of Music

An oral history of WWOZ’s legendary “Treehouse” studio

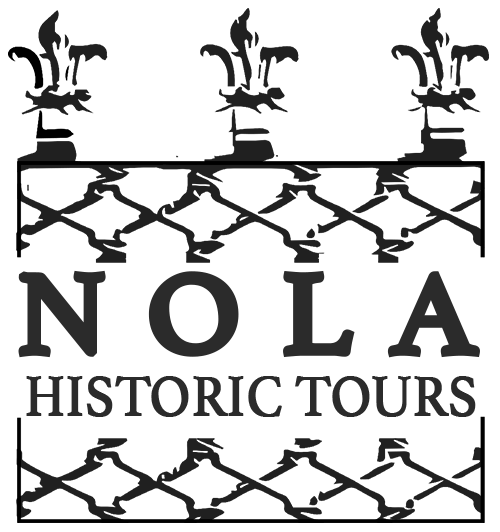

COURTESY OF WWOZ, PHOTO BY AL KENNEDY

Dr. John visits the “Treehouse” during the spring 1999 pledge drive.

This piece was edited by WWOZ’s Dave Ankers and 64P’s Brian Boyles, Romy Mariano, and Toan Nguyen.

Interviewees

Maryse Dejean was a staff member and show host at WWOZ during the “Treehouse” years. She is currently Volunteer Coordinator at the station.

Bob Dylan is Bob Dylan.

David Freedman has been the General Manager of WWOZ since 1992.

Dan Meyer is a traditional jazz show host on WWOZ, heard on Mondays from 9 to 11 am. He started volunteering at WWOZ in 1981, and is the second longest serving show host at WWOZ, after Hazel the Delta Rambler.

“Big D” Dennis Schaibly began as a volunteer at WWOZ in 1992 and has been an on-air show host since 2000.

Beginning with a Parade

After years of work by brothers Jerry and Walter Brock, along with a dedicated group of fellow music lovers, on December 4, 1980, WWOZ secured a federal permit to broadcast. The station still didn’t have a physical home. The transmitter and antenna had already been installed and tested at the tower, in Bridge City. A few weeks later, the Brocks set up a studio in an apartment above Tipitina’s, the now legendary nightclub that opened in 1977 at the corner of Napoleon Avenue and Tchoupitoulas Street in Uptown New Orleans.

Dan Meyer: It was a small sort of rundown apartment above Tipitina’s music club, sort of in a shotgun layout. It had a bathroom right up the stairs that didn’t always have running water. They had two rooms–sort of a larger long room, then a small room–that were the studios. Reel to reel tapes, LPs and microphones and turntables. I can’t remember if we got a CD player right before or just after we moved, one way or another, but CDs were not yet a big thing even if they had technically been invented. And no air conditioning, so it often had the sound of the buses on Napoleon Avenue going by.

I remember a couple weeks in a row when I had the first shift in the morning I found a mouse in the wastebasket. And what Walter Brock taught me to do was just take it and fling it out the front window. And I did that a couple times, and next time I came by, there was a mouse in the wastebasket again, I presume the same one got in and got caught more than once.

On October 28, 1984, the station moved from the apartment above Tipitina’s to its new home in Armstrong Park. Like any significant event in New Orleans, the occasion warranted a parade.

Dan Meyer: We had some people at both studios, to do the on-air switchover. But then we also had two different parades. We had a motor parade, starting at the Napoleon Avenue studios, and going to Armstrong Park, of people in their cars and some pickup trucks and small vehicles, decorated, and I think a couple musicians were playing on a couple of them, with banners hanging off them to let people know about WWOZ and moving to the new place.

“It was literally an oasis of music. A separate world that you walked into when you got into the courtyard there and into the building. It was a magical separation between the entire real world and a world dedicated wholly to New Orleans music.”

And then also for the inauguration of the Treehouse, they had the 90.7 Piece Brass Band. We had a shout out for any brass band musicians we could get to join in with a small hired band to parade around Armstrong Park, to mark WWOZ being there. And the .7 was a seven-year-old Grand Marshal. And we had about 90 people, a big brass band. A few people on washboards filling in. I believe Wynton Marsalis showed up for that, playing his Monette trumpet.

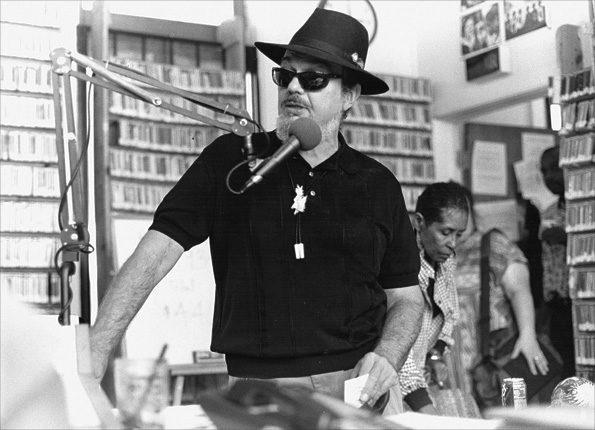

Maryse Dejean: The Treehouse was inside Armstrong Park on the St. Philip Street side, and it was a two story building. Downstairs we had a small reception area where we had a couple of workstations,and then as you entered on the left hand side there were all the mailboxes for the show hosts. On the right-hand side was a bit of a “dungeon-esque” room, which served as our production room. And then you went up a stairwell to the second floor where there was a bathroom where every musician, artist, or cultural warrior longed to post their picture. All the bathroom walls were collaged with very hip photographs of different artists, different events and so forth. And I had a very tiny office right next to the bathroom.

And then as you continued to walk down the hallways there was the control room, which had these very large windows to the side, which you can see to this day, with WWOZ’s call letters, as you drive down St. Philip Street.

Treehouse Floor plan, courtesy of WWOZ and the Archive of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival and Foundation.

Dan Meyer: The downstairs had a tape library and extra library of stuff we didn’t use all that often. And we had a pre-recording studio we could use, and record shows on reel to reel tape. I believe Walter and/or Jerry Brock had an apartment right across St. Philip Street that also served some office functions.

David Freedman: The building we were in was called the Kitchen Building because it served as the commissary for the adjacent Perseverance Hall. There are two or three other beautiful Creole buildings in that complex that were dragged onto the site much later, so you’d have to check with an historian to verify the actual date of the Treehouse. [Editor’s note: Perseverance Hall is a two-story structure built in 1820 as a Masonic lodge; per this New Orleans Advocate article, it is the oldest lodge building still standing in the U.S.]

Well, operationally it was a dream, and it was a nightmare. A dream because it was the center of the Treme universe, and everybody poured in, and we were in this paradisiacal park, which was just a drop-dead gorgeous place to be. Operationally it was a nightmare. First of all, like all of our spaces we’ve ever had, it was way too small. It was only three rooms, to run a radio station from. And we had hundreds of volunteers and hundreds of people streaming through there, artists, guests, and so forth.

Dan Meyer: When we’d have people play live in the studio we didn’t have a separate room, with a window and glass and everything. I remember once we had a 13 piece band and we had two microphones, and I had to just do like I was directing traffic, and wave people further away and gesture to get them to come closer to the microphones, to get a rough balance by holding earphones to my head.

“Big D” Dennis Schaibly: It was literally an oasis of music. A separate world that you walked into when you got into the courtyard there and into the building. It was a magical separation between the entire real world and a world dedicated wholly to New Orleans music.

“Syringes and condoms littered the path to the station door. One stormy night, someone drove their pickup truck into the lagoon. As the manager of the radio station, I didn’t sleep well at night.” David Freedman

David Freedman: Also the security was just dreadful. We were in an isolated section, where at one point the gate was locked behind us and the only way to get out was to go clear across the park. And another time we were going through the gate but the gate was locked and we had to sit there and unlock it. And people were constantly being “approached.” We had cars that were broken into.

There was a sense in the air that at any moment something could happen. In truth, the station seemed to be miraculously protected even as mayhem set loose all about us in the neighborhood. Syringes and condoms littered the path to the station door. One stormy night, someone drove their pickup truck into the lagoon. As the manager of the radio station, I didn’t sleep well at night. Because there was no way I could protect my volunteers and employees from what seemed to be lurking around us.

The station attracted on-air personalities who made the Treehouse–and WWOZ’s pledge drives—vibrate in more ways than one.

Maryse Dejean: Andy White who did the Swing Session…had 78s, and at the time we didn’t have the capability of playing 78s on air, so Andy White would come with all of his 78s, and a small turntable that played 78s, and he would tip the microphone down and that’s how the sound carried over on the airwaves. He played it through the microphone.

Ernie K-Doe introduces Johnny Adams

Audio Player

Ready Teddy was always very high energy, very jovial. When he put his mind to it he could do an amazing show. A New Orleans music show or a blues show. He could do amazing stuff. He introduced me to the Dixie Cups. He was close friends with Little Richard, and claimed to be the inspiration for his song “Ready Teddy.” [Editor’s note – Little Richard recorded the song in 1956; the future DJ was then eight years old.]

Ready Teddy McQuiston’s high energy hand stand while in the booth, 1993 Courtesy of WWOZ, photo by Al Kennedy.

Bob Dylan [from his 2004 memoir Chronicles, Volume One, describing his time living and recording the album Oh Mercy in the city in 1989]: My favorite DJ, hands down, was Brown Sugar, the female disc jockey. She was on in the midnight hours, played records by Wynonie Harris, Roy Brown, Ivory Joe Hunter, Little Walter, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Chuck Willis, all the greats. She used to keep me company a lot when everyone else was sleeping. Brown Sugar, whoever she was, had a thick, slow, dreamy, oozing molasses voice–she sounded as big as a buffalo–she’d ramble on, take phone calls, give love advice and spin records. I wondered how old she could be. I wondered if she knew her voice had drawn me in, filled me with inner peace and serenity and would upend all my frustration. It was relaxing listening to her. I’d stare at the radio. Whatever she said, I could see every word as she said it. I could listen to her for hours. Wherever she was, I wished I could put all of myself in there.

Listen to Brown Sugar interview Bobby Blue Bland

Audio Player

David Freedman: First of all it was a great space. It was big enough to accommodate a piano and musicians, and literally calling it a “treehouse” — you felt like you were up in kind of like a clubhouse. It was the best environment I’ve ever had for a pledge drive. That’s where we developed the whole aesthetic of music and testimony….

When I [joined the station] in 1992, the pledges were boring and terrible and the most they ever raised in a given pledge drive was $20,000, that was considered to be a really good pledge drive. And the income that year was $40,000 from two pledge drives. And they were terrible pledge drives. And so we started really jazzing it up and making it a party and having fun with it and having music and just getting loose. And pretty soon we went way, way beyond that.

Maryse Dejean: Snooks Eaglin was a regular during our pledge drives. We’d have Popeye’s chicken and Taaka vodka ready for him.

“Big D” Dennis Schaibly: There were things that happened in the Treehouse that never could happen any other place. Best example: we were having a pledge drive show in 2004. It’s Tuesday and we’re talking about Snooks [Eaglin, legendary guitarist] coming in for Billy Delle’s show on Wednesday night. And he’s gonna be in the studio, and all the people want to be there. And literally we’re sitting outside the front door and we said “Why don’t we just throw a big party out here in the courtyard?” And we got on the phone, we got a group called the Brotherhood of Groove to come and be the house band, and we set the whole program out on the back porch of the family house next door. And Snooks came and played, Eddie Bo came and played, George Porter was there, Glen David Andrews, John Boutte came and sang, and it was just a big party. People brought food and it was just a big neighborhood gathering. But it could happen only in that little alcove of separation from the rest of the world.

Maryse Dejean: One particular pledge drive, one morning Bob French was doing Big Mama’s show. Bob had invited a multi-piece brass band from some European country, they might have come from Germany. And there was one volunteer answering the phones for pledge drive. That person had to leave the room and go downstairs and open the door for the brass band. And the band came up the steps and went upstairs. They began to play, the phones rang like crazy. But there was no way for the phone volunteer to get into the room to go answer the phones, because the brass band was so large! And the instruments were so bulky!

WWOZ’s open door policy for musicians cemented its role as a community station where listeners could expect the unexpected. Musicians including the fiery Bob French and the inimitable Ernie K-Doe hosted shows, and the Treehouse was the site for impromptu live performances by significant New Orleans artists like Snooks Eaglin and Trombone Shorty.

Dan Meyer: Snooks Eaglin was a good friend of the station who came in a number of times. And one of my favorite stories is one time there was a jug skiffle band called the Bad Oyster Band that I’d arranged to come in to use the downstairs to prerecord a couple tracks that I’d then play via tape on my show. On another day. But we got in there and there was this stomp-stomp-stomp on the ceiling, and it was so loud that we couldn’t record there. So we wandered on upstairs, and Snooks Eaglin was playing live on someone else’s show. And one of the players in the Bad Oysters started fingering his mandolin, playing in less-than-whisper volume the tunes Snooks was playing, and he didn’t think anyone could hear. But of course Snooks Eaglin [who was blind] picked it right up and said, “Hey, who got that mandolin? Hey, come on in here and play with me! ” So they all wound up jamming over the air.

Listen to Ready Teddy interview Maceo Parker

Audio Player

Maryse Dejean: I remember once the very small Trombone Shorty knocked at the door with his little bandmates, and Trombone Shorty said that he wanted to come up and plug their gig. He was about nine years old.

“WWOZ was the kind of station I used to listen to late at night growing up, and it brought me back to the trials of my youth and touched the spirit of it.” Bob Dylan

David Freedman: Mr. Google Eyes, Danny Barker, Earl Turbinton aka the African Cowboy, Joe Jones, Ernie K-Doe, Earl King, Eddie Bo, Snooks Eaglin, Dr. John, Allen Toussaint and though he wasn’t a musician, Ray Dolby who couldn’t believe that all this magic was coming from such a funky space.

Maryse Dejean: I walked in there one day when they had just renovated the Perseverance Hall next door, and there was some sort of inaugural event or ribbon cutting ceremony. And I opened the door to go into the studio and sitting right there in the reception area was Earth Wind & Fire.

George Benson came through, and Billy Dee Williams, and Dionne Warwick. And they were all really fascinated by WWOZ, they all loved WWOZ.

Bob Dylan: WWOZ was the kind of station I used to listen to late at night growing up, and it brought me back to the trials of my youth and touched the spirit of it. Back then when something was wrong the radio could lay hands on you and you’d be all right…

Maryse Dejean: Allen Toussaint would come by, and one evening, because they locked the St. Philip Street gate when it started to get darker, and Allen had parked his Rolls Royce outside the gate. When he finished his interview on Billy Delle’s show and came out, the gate was already locked! And I happened to be there working late, and he said, “Oh, can you help me? The gate is closed!” So I said “Don’t worry,” and I called up security and they came and opened up the gate, and he was so grateful, and appreciative. He turned to me and said “Thank you so much! I’m Allen, by the way.” And I said, “Yes sir, I know you’re Allen!”

The impact of Hurricane Katrina led to the demise of the Treehouse and to WWOZ’s relocation to the French Market. Click here to listen to a special episode of “New Orleans Calling” for a history of that period as told by DJs, musicians, and other members of the WWOZ family. The show is produced by George Ingmire and Dave Ankers.

“Big D” Dennis Schaibly: You were able to walk through those doors and just leave everything, the rest of the world, outside. And just immerse yourself in New Orleans music and leave all those troubles behind.