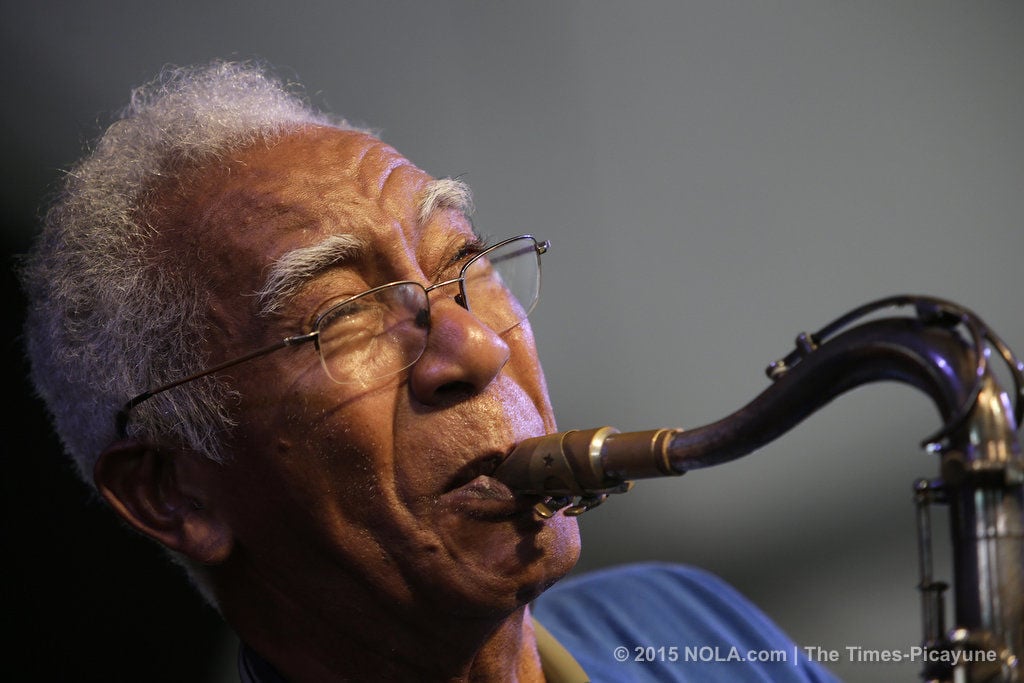

New Orleans avant-jazz saxophonist Kidd Jordan improvises his way to $50K fellowship

Kidd Jordan & the Improvisational Arts Quintet perform in the Zatarain’s / WWOZ Jazz Tent at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival in New Orleans on Friday, April 24, 2015 in New Orleans. (Photo by Chris Granger, Nola.com | The Times-Picayune)

- CHRIS GRANGER

New Orleans avant-jazz saxophonist Edward ‘Kidd’ Jordan.

- PROVIDED PHOTO BY JIM THORNS

Kidd Jordan warms up with his family at his daughter’s home in New Orleans on Sunday, October 16, 2016.

- Photo by Chris Granger, Nola.com | The Times-Picayune

Kidd Jordan, center, with his musically-talented children, from left to right, Kent, Stephanie, Rachel, and Marlon in New Orleans on Sunday, October 16, 2016.

- Photo by Chris Granger, Nola.com | The Times-Picayune

Avant-jazz saxophonist and educator Edward “Kidd” Jordan didn’t always get paid.

Audiences and venue owners sometimes responded poorly to his adventurous, mostly improvised approach to jazz, which prioritizes being in the moment more than melody.

“Some people liked it, and some walked out,” he recalled recently. “They’d say, ‘Y’all play that crazy music. Y’all crazy.’ We were, but it developed into something.”

Staring down an empty venue, he’d prep his bandmates with, “We’re going to play for the seats tonight.”

But, he said, “I’d see the seats dancing.

“Come hell or high water, whether you were making a million dollars or you knew they were going to run out with the money and you weren’t getting paid, it was the same thing: we played, and we had a great time. If you get a dollar, you get a dollar.”

This week, United States Artists, a Chicago-based arts funding organization, named him to its 2021 fellowship class. The fellowship comes with a $50,000 grant.

To the 85-year-old Jordan, who also helped mold countless young musicians during his decades as a teacher, this late-career recognition for his “crazy” improvisational style is especially gratifying.

Maybe, he said, “it’s not so crazy after all.”

****

Kidd Jordan’s music was never too extreme for at least one listener: He and his wife, Edvidge Chatters Jordan, have been together for more than 60 years.

“She comes from a musical family,” he explained.

At 85, his health has slowed him down. “I’m feeling my age. I’m hanging in there, for an old man. I’ve been over a lot of mountains. If you live a long time, a whole lot of things happen to you. Just keep living.”

He aspires to play his main tenor saxophone every day, though some days he just cleans it. “Every day I try to do something. If I play two minutes or I play an hour …”

PROVIDED PHOTO BY ERIC WATERS

The duration of his daily playing is a barometer of his health.

“If he’s not practicing, we know something is wrong,” said Rachel Jordan, one of his daughters. “That’s how we know we’ve got to bring him to the doctor.”

He’s always tried to take care of himself.

“I never did drink,” he said. “Other musicians asked, ‘Kidd, why don’t you drink?’ ‘I’m trying to make 100.’ They laughed. But the majority of them passed away.”

Born in Crowley in 1935, Jordan picked up the saxophone early. “If I hadn’t discovered music when I was young, I don’t know what I’d be doing,” he said.

In New Orleans, he spent time in the Hawketts, though not when the rhythm & blues band recorded “Mardi Gras Mambo.”

Education was, and is, a priority. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Southern University and a master’s in music from Millikin University in Illinois.

In New Orleans, a city built on traditional jazz, Jordan carried the torch for the avant-garde. Intent on pushing boundaries, he founded the Improvisational Arts Quintet to play “new New Orleans music.” The title of the group’s debut album spoke to its philosophy: “No Compromise!”

Jordan scoffed at musicians who tried to sound like legends Charlie “Bird” Parker or John “Trane” Coltrane. His music might be “crazy,” he said, but “it’s mine. It’s not Charlie Parker.”

“If you play what Coltrane and Charlie Parker played … ain’t nobody going to play like Bird and Trane. You better do what you do. I’m serious about that.”

He’s also serious about educating the next generation. In 1955, he landed his first teaching job, at Bethune High School in Norco.

In 1972, he embarked on a 34-year stint at Southern University at New Orleans. He retired as chairman of the university’s jazz studies program in 2006.

He’s also been artistic director of the Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong Summer Jazz Camp since its 1995 inception. He founded the Kidd Jordan Institute of Jazz and Modern Music to instill his sense of artistic freedom in others. He’s also tutored scores of private students.

The goal was “was not to teach them jazz, but to teach them how to play their instrument, and then let them go.”

Photo by Chris Granger, Nola.com | The Times-Picayune

Prominent former students include Wynton and Branford Marsalis, Donald Harrison Jr., Tony Dagradi, Jon Batiste, Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews and “Big” Sam Williams.

He also taught his own children, emphasizing the need to practice and then practice more. Four of the seven became professional musicians: Kent on flute, Stephanie as a singer, Rachel as a classical violinist and Marlon on trumpet.

The senior Jordan plays “what comes off the top of my head. Everything I do is original. I just pick up the horn and start playing.

“I’m playing jazz, and jazz is supposed to be improvisational music. You’ve got to stick to your principles.”

The squawks, honks and nonlinear progressions that tumbled from his horn sometimes cleared a room. Certain club owners would say of his band, “If you want a house that’s empty, just call them.”

Eventually, though, “that crazy music don’t sound so crazy. That’s improvisation. That’s what jazz is supposed to be. It’s your opinion against mine. I’m going to keep on doing the crazy music.”

He toned down to back the likes of Cannonball Adderley, Ornette Coleman, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin and Stevie Wonder. But with his own bands, he followed his instincts wherever they led. Because his teaching income supported his family, he didn’t need to try to please audiences.

“If you depend on playing music” to earn a living, he reasoned, “then you’ve got to depend on what people want you to play.”

Jordan has collected his share of honors. The French Ministry of Culture anointed him a knight, or chevalier, of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1985. OffBeat magazine made him the first recipient of its lifetime achievement in music education award. In 2017, Loyola University awarded him an honorary doctor of music degree.

Becoming a United States Artists fellow is a different kind of honor. “It’s an honor,” he said, “and a check.”

Since its founding in 2006, United States Artists has given a total of $33 million to 700 individuals representing such creative disciplines as music, architecture and design, writing, dance, film and visual art.

Jordan joked that the organization chose him because “this old man has been scuffling all these years.”

In announcing Jordan’s award, United States Artists recognized that he is “internationally acclaimed as one of the true master improvisers still performing today.”

PROVIDED PHOTO

He hasn’t been able to perform publicly since the coronavirus shutdown. But just before the lockdown commenced in March 2020, he recorded a double album, “Last Trane To New Orleans,” with drummer Mark Lomax, saxophonist Eddie Bayard, keyboardist Darrell Lavigne and trumpeter Marlon Jordan.

Rachel Jordan produced the recording session at McDonogh 35 Senior High School and released “Last Trane to New Orleans” in July through her RJ Records. On it, her father is as uncompromising as ever, as he engages in “spontaneous composition,” i.e. improvisation.

He intends to continue improvising as long as he can.

“I’m always dealing with something. I won’t ever stop dealing with music. I feel like I’m just getting started. If my health was better, I’d be doing much more.

“I’m not tired of music, believe me. I’ve got enough stuff to keep me busy the rest of my life.”